Straddles and strangles are slightly more complicated strategies than trading delta – but still among ways to start using the potential of options trading.

Like most other options strategies, both straddles and strangles use a combination of calls and puts.

While delta spreads let you take advantage of static markets, buying a straddle or a strangle allows you to maximise your profit when the market is volatile. The more volatile it is and the more the market moves in one direction, the greater your profits can be.

How to use a straddle

A straddle involves simultaneously buying both a put and a call option on the same market, with the same strike price and expiry. By doing this you can profit from volatility, regardless of whether the underlying market moves up or down. But there is a risk – if no volatility occurs, you’ll lose your premium.

A straddle purchases puts and calls with the same strike price and time period.

For example, let’s say you expect a large move from Wall Street, but you’re not sure which way it will go. The June Wall Street contract is currently trading at 25000.

To set up a straddle, you’d buy both the June 25000 put and the June 25000 call. If the cost to buy each of these is 1000 points, your total cost is 2000 points x your stake size.

If the June Wall Street contract stays where it is you lose the premium. If it drops to 20000, the call will expire worthless, but the put will make enough money to more than cover the cost of the entire position – the premiums paid for taking out both options. If the value of the June Wall Street contract rises to 28000, you can use the call option – the put will be worthless, but the call should provide a profit.

What about a short straddle?

With a short straddle you can benefit if volatility collapses, by selling both the calls and puts. The strategy behind the short straddle is reaching a breakeven point where the underlying asset is either at the money (the strike price) or out of the money. This would be below the strike price for a call option but above the strike price for a put option. In either case, the option contract would expire worthless. The gain for you will be the profit you collect from the option premium.

The risk in a short straddle strategy is unlimited, as the underlying asset price could move up or down well beyond the strike price of either option.

Should you be using a straddle?

So is the time right for a straddle? Ask yourself: is the market static? Does it look as though it could remain so?

If the answer is no, if might be time to look at a long straddle.

Do you believe that volatility will collapse? In that case, it might be time to consider a short straddle.

Strangle

A strangle is a similar strategy, but here you buy a call with a slightly higher strike price than the put. This means that you need a larger price move to profit, but you will typically pay less to open the trade because both options are purchased when out of the money.

A strangle’s key difference from a straddle is therefore in providing greater flexibility of balancing the cost of opening a strangle versus a probability of profit. So, given the same underlying security, strangle positions can be constructed with low cost and low probability of profit, or higher cost and a higher possibility of profit.

A strangle purchase involves puts and calls that are separated by at least one strike price in the same time period.

It involves buying a call option with a strike price that is slightly out of the money plus a put option with a strike price that is slightly out of the money.

Long or short?

Strangles can be either long or short.

In a long strangle, you buy the calls and puts.

The strategy is to profit if the underlying asset makes a move in either direction.

You’d use a long strangle if you’re expecting the underlying security to make significant price moves, such as in advance of an earnings announcement. Your profit potential is virtually unlimited, and your risk is limited to the option price you pay.

So, for example, suppose you see that the FTSE 100 has been in a tight range for a few weeks, and believe it’s due to break out of this pattern. The index is currently trading at 6500. You think that there will be a large move over the next few months, so decide to buy a three-month 6700 call priced at 25 and a three-month 6300 put priced at 30. You buy one contract ($10 lot size) of each. The total cost of this is $250 + $300 = $550. This is your maximum risk.

In three months’ time, the FTSE has surged after positive economic data, reaching 6800. At this point, the 6300 put is worthless but the 6700 call is worth 100. You therefore realise a profit of $450 on this strategy. This is equal to the profit made on the 6700 call (100 – 25 x $10) minus the loss on the 6300 put (30 – 0 x 10).

Profit = price of underlying (6800) – strike price of long call (6700) – net premium paid (55) = $450.

Even though you’ll have to let the put option expire worthless, you’ll still have to count the cost of your option premium when calculating your profit.

What about the risks vs the rewards?

With a long strangle strategy, the maximum profit is unlimited because, theoretically, there is no limit to how high the underlying asset’s value can rise. On the put side, the underlying price can only go to zero, capping your profit if it does so.

However, your risk is limited to the option premium.

Should you be using a strangle?

So is the time right for a strangle? Ask yourself: is the market volatile? Does it look as though it could experience some major moves?

If the answer is yes, it might be time to look at a long strangle.

If the answer is no, you might want to consider a short strangle.

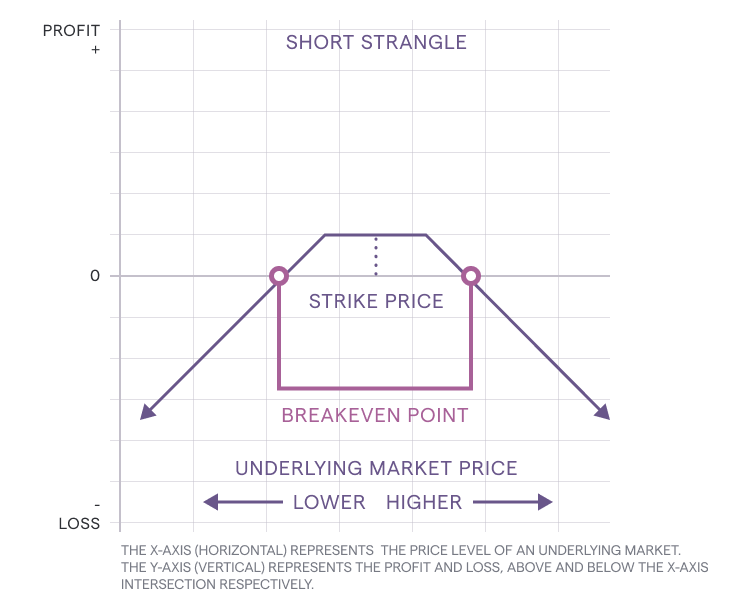

In a short strangle, you are selling the calls and puts.

You are predicting the underlying price will show little volatility, remaining somewhere between both strikes you select, so that the options you sell will expire worthless.

The profit potential is limited to the net credit you earn from the premium you collect. But the risk is virtually unlimited because, in a worst-case scenario, you would be responsible for the options.

So back to the FTSE 100. Let’s say a period of geopolitical uncertainty has been resolved, and with the UK in calmer waters you feel that that the index could be ready for a pause in volatility and will trade in a tight range for the foreseeable future.

The price of the FTSE 100 is currently 6500. You sell a three-month call option with a strike price of 6800, at a price of 10. Plus you sell a put option, also expiring in three months’ time, with a strike price of 6100, at 15. You sell one contract ($10 lot size) per point, so you stand to make a maximum profit of $250.

How does this play out?

If the FTSE finishes between 6525 and 6075 in three months’ time, you will keep the $250 premium. For every point that the FTSE finishes above 6825 or below 6075 at expiry, you’ll lose $10 per point (since you sold one contract with a $10 lot size of the call and the put).

What about the risk?

As the seller of the option, your maximum risk is virtually unlimited.

Homework

Which markets are volatile right now? How might you use a straddle or strangle to profit from that volatility?

Test out your idea in your demo account. Log in now to give it a try.

Lesson summary

- Straddles and strangles provide a way of trading when assets are volatile

- Buying a straddle and strangle allows you to maximise your profit when the market is volatile – and the more volatile it is, the greater your profits can be

- Straddles involves simultaneously buying both a put and a call option on the same market, with the same strike price and expiry date

- A strangle purchases puts and calls that are separated by at least one strike price in the same time period

- A strangle offers more choice, and can be set up with low cost – low potential profit, or higher cost – higher potential profit